Cas Weykamp博士,现任荷兰贝娅特丽克丝女王医院的临床化学家、荷兰室间质评计划负责人、IFCC HbA1c参考实验室网络联络官、IFCC HbA1c整合计划成员、美国AACC一致性计划研发组主席、NGSP执行委员会成员、上海市临床检验中心学术顾问,是国际知名的糖化血红蛋白研究专家,致力于建立HbA1c参考体系、推进HbA1c检测的全球标准化。

The need for standardisation derives from the success of HbA1c: the diagnostic industry well recognised the importance of (and the market for) HbA1c. Many methods in many more commercial versions have been developed. All have their own specificities and, unfortunately, their own reference ranges. This broad variation in test-results raised the need for standardisation[ 6].

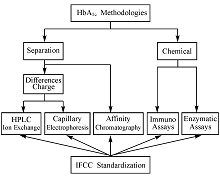

There are 2 mainstream analytical concepts, one based on the separation of haemoglobin fractions, the other on specific chemical reactions (Figure 1). HbA1c and non-glycated haemoglobin (A0) have different electrochemical properties, which allow separation of the respective fractions and quantification of HbA1c as fraction of total haemoglobin. This concept is applied with ion exchange chromatography, capillary electro-phoresis, and affinity chromatography. Due to the attachment of glucose to the β-valine terminal, the isoelectric point of HbA1c differs 0.02 pI units from A0. The difference is enough to allow separation with ion exchange chromatography but also that small that only dedicated high performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) instruments perform satisfactory[ 6]. Capillary electrophoresis also uses differences in charge. A high voltage (10.000 volt) electrical field and electro osmotic flow force separation[ 7]. Haemoglobin molecules with a glucose attached have affinity to boronic acid. In a column filled with boronic acid coated particles, HbA1c will be delayed while HbA0 runs freely through the column. This results in 2 fractions, glycated and non-glycated, and is the principle of affinity chromatography[ 8]. Chemical methods require 2 independent assays, one for HbA1c and one for total haemoglobin. HbA1c is measured using a specific chemical reaction. In immuno assays an excess of anti-HbA1c antibodies is added to a sample. Antibodies bind to HbA1c and their excess is agglutinated. The resulting immune complexes lead to cloudiness, which is measured turbidimetrically or nefelometrically[ 9]. In enzymatic assays a protease is used to cleave the β-chain. The resulting peptide reacts with an oxidase and the HbA1c concentration is measured by determining the resulting hydrogen peroxide. In both immunochemical and enzymatic assays, total haemoglobin is measured photometrically[ 10].

Specificities and selectivities of commercial methods are different and therefore there is a broad variation in (uncalibrated) outcome of HbA1c tests. The first years after the discovery of HbA1c, each method or even each laboratory had its own reference values.

Figure 1 Analytical Concepts of HbA1cMethods and Their Traceability to the IFCC-RMP

For optimal clinical use (uniform clinical guidelines, comparison of scientific studies) equivalence of results is desirable. Equivalence can be achieved with harmonization or standardi-zation[ 11]. With harmonization commercial methods are calibrated against an arbitrary chosen so called designated comparison method. With standardization calibration is against a scientifically sound reference method, a so called reference measurement procedure. One could also say that harmonization leads to a relative truth and standardization to the absolute truth. The need for equivalent results was well recognized and inspired several national harmonization initiatives. In the US the arbitrary chosen method was the method used in the DCCT and a nationwide program with international affiliations was (and is) organized by the NGSP[ 12]. Similar initiatives achieved harmonization in Japan (JDS/JSCC) and Sweden (Mono-S)[ 13, 14]. Unfortunately all were based on designated comparison methods and it is not surprising that results of these arbitrary chosen methods were different. This situation caused confusion and therefore the IFCC developed a reference method to achieve worldwide standardization.

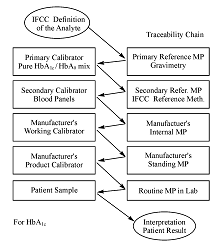

The IFCC Reference Measurement Procedure (IFCC-RMP) is based on the concept of metrological traceability (Figure 2). Pure HbA1c and HbA0 are mixed to prepare primary calibrators that are used to calibrate the IFCC-RMP. Erythrocytes are washed and lysed, followed by enzymatic cleavage[ 14, 15]. The resulting hexapeptides are quantified with either HPLC-mass spectrometry or HPLC-capillary electrophoresis. With the IFCC-RMP values are assigned to whole blood panels that serve as secondary calibrators for manufacturers. The IFCC-RMP is embedded in global network of reference laboratories[ 16]. The Shanghai Center for Clinical Laboratory (SCCL) was the first approved chinese laboratory in the global network.

Figure 2 The Metrologic Traceability Chain for HbA1c

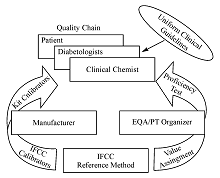

Figure 3 shows the complete quality chain. With the IFCC-RMP values are assigned to the IFCC calibrators. These are used by the manufacturers to assign values to their kit calibrators, subsequently used by the clinical laboratories to calibrate their instruments. This chain warrants that worldwide HbA1c results reported to diabetologists and patients are traceable to the IFCC reference method, allowing global guidelines with uniform decision limits for diagnosis and therapy. Independent control is achieved by external quality assessment/proficiency testing (EQA/PT) organizers using samples to which values have also been assigned with the IFCC-RMP.

The manufacturer uses calibrators, to which values have been assigned with the IFCC-RMP, to assign values to the kit calibrators. The EQA/PT provider uses samples also targeted with the IFCC-RMP. Good performance of the whole chain is demonstrated when the laboratory (clinical chemist), using the kit calibrators of the manufacturer, measures the correct HbA1c in EQA/PT samples. Then all results of patients are traceable to the IFCC-RMP and diabetologists can use universal reference values and decision limits.

Figure 3 Quality Chain of IFCC-RMP

Standardised HbA1c Testing

In the medical laboratory it is common that, once a reference method has been established, patient results are expressed in the units of that reference method. In case of HbA1c chemists adopted the units of the IFCC-RMP but in some parts of the world (especially US) there was resistance of clinicians: they were used to the NGSP units and did not want to change. This was a dilemma solved in a summit meeting of IFCC, IDF, EASD and ADA: the IFCC-RMP is the only valid anchor for standardization of HbA1c but on patient reports HbA1c will be reported in both IFCC (mmol/mol) and NGSP (%) units[ 17]. NGSP units are derived from IFCC units using a master equation. Reporting in two units is not practical in daily life and therefore many countries use either IFCC or NGSP units. Table 1 shows standard interpreation norms in both units. Instruments have both options and journals follow the consensus statement and publish parallel in both units. The master equations to convert IFCC into NGSP-units [NGSP(%)=0.0915X IFCC (mmol/mol)+2.15] and vice versa [IFCC (mmol/mol)=10.93NGSP(%)-23.5] are established and monitored by the networks of IFCC and NGSP[ 16].

| Table 1 Standard Interpretation Norms |

HbA1c is the ultimate longitudinal parameter: therapy of a patient depends on serial measurements of HbA1c over a period of years or even decades. For this reason quality management should be given much attention. Aspects are pre- and post-analytical considerations, the quality system, and performance goals. Point-of-care tests(POCT), operated outside the laboratory should be given specific attention.

Contrary to glucose, the sample collection and storage of HbA1c is robust. Blood can be taken any moment of the day without any precautions of the patient. Blood obtained by venipuncture or finger-stick capillary is suitable. Unless otherwise specified by the manufacturer the anticoagulant should be ethylene diamine tetraacetic acid (EDTA). Sample stability is method specific with methods based on differences in charge being most sensitive to ageing effects on the results. Some POCT cannot measure when the specimen is even only slightly haemolysed. But in general blood is stable up to 1 week in the refrigerator (2-8 °C). Frozen below -70 °C blood is stable for at least a year. It should be stressed that storage at -20 °C has adverse effects and should be avoided[ 20]. Some manufacturers developed method-specific collection systems to facilitate the logistics after field-collection (e.g. filter paper and micro cups with lysing buffer). These systems should only be used if validated in comparison with standard collection[ 21].

Results below the lower limit of the reference interval should be confirmed with repeated testing. If confirmed, the clinician should be informed on the possibility of a variant or shortened red cell survival. Samples with extreme high results (>140 mmol/mol; >15%) and results that do not match with the clinical picture should also be re-assayed. Repeated testing with a method of a different analytical principle can be of help to trace the reason for unexpected results (patient- or method related).

In qualified laboratories a quality system consisting of three basic ingredients is in place: accreditation to ISO 15189, internal quality control and external quality control. For internal quality control, 2 control materials (low and high HbA1c) should be assayed in every analytical run with results within pre-defined limits. Frozen whole blood aliquots stored below -70 ℃ and lyophilised haemolysates with no or known matrix effects are suitable[ 21]. Participation in an EQA (also: PT) provides valuable external information to manage the quality of HbA1c: bias is derived from the EQA target set with the IFCC-RMP, performance is compared with other laboratories using the same method and EQA reports are an up to date review of available methods and their performances.

The reliability of an HbA1c result depends on bias (related to proper calibration) and precision (related to the reproducibility of the method). Quality goals can be derived from biological variation, clinical needs or the state of the art. For HbA1c a generally accepted rule of thumb is that clinicians interpret a difference of 5 mmol/mol (0.5%) between successive patient samples as a significant change in glycemic control[ 22]. From this clinical need, it can be calculated that the intralaboratory CV (derived from the lab's internal quality control records) should be <3% (<2% NGSP units). The interlaboratory CV (derived from the EQA review) should be overall <5% (<3.5% NGSP units) or <4.5% (<3% NGSP units) within one method[ 21].

The quality concept used in laboratories can not be applied in POCT settings. Careful reading of the instructions, check if the manufacturer warrants traceability of results to the IFCC-RMP, and periodic exchange of samples with a qualified laboratory contribute to the quality.

Due to the IFCC and NGSP standardisation and on-going efforts of the diagnostic industry, HbA1c has much improved since the landmark clinical trials (DCCT, UKPDS) clearly demonstrated the relationship between glycemic control, HbA1c and diabetic complications. HbA1c is now a reliable test and as such an indispensable tool in both routine management and diagnosis of diabetes. But there are still things to do. Global availability of adequate methods, traceable to the IFCC-RMP has not been achieved yet. Although the IFCC-RMP has been adopted as the only valid anchor to standardise, HbA1c is still reported in several different units: universal reporting in IFCC-units remains a challenge. Quality management in laboratories needs to be improved. The use of POCT instruments is controversial. Only a few devises meet acceptable performance criteria, even in the hands of laboratory professionals[ 23]. The quality of testing by non-laboratories is questionable: as long as participation in an EQA programme is not mandatory, no objective information on performance in the real world is available. Improvement of the tests and development of a quality concept to warrant acceptable performance by non-laboratory staff is a challenge. And finally, education, education: for the management of diabetes more and better tools are available now, but there is still much to be learned for laboratories and clinicians on standardisation, quality management and how to use HbA1c to achieve the best patient care.

[23] Lenters-Westra E, Slingerland RJ. Six of eight haemoglobin A1c point-of-care instruments do not meet the general accepted analytical performance criteria[J]. Clin Chem,2010,56(1):44-52.

| [1] |

|

| [2] |

|

| [3] |

|

| [4] |

|

| [5] |

|

| [6] |

|

| [7] |

|

| [8] |

|

| [9] |

|

| [10] |

|

| [11] |

|

| [12] |

|

| [13] |

|

| [14] |

|

| [15] |

|

| [16] |

|

| [17] |

|

| [18] |

|

| [19] |

|

| [20] |

|

| [21] |

|

| [22] |

|